You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Economic Earning/Accounting Earning

- Thread starter Anuja

- Start date

Hello @AnujaHi, please explain me the difference between Economic earning & Accounting earning..

Please note that I moved your thread here, as you had it posted under the "Posting in the forum" thread, which is a thread that explains where you should post questions. I've used the search function to try to find other threads that discuss your question, and I also searched the current FRM curriculum. Can you be more specific about the current reading that you are studying in the FRM curriculum so I can move your post to the correct section of the forum? I was unable to find the terms you have asked about anywhere in the curriculum.

Thank you,

Nicole

@Nicole Seaman Thanks for looking. The relevant LO is "Evaluate some advantages and disadvantages of hedging risk exposures." under the R2 reading (Crouhy Chapter 2. Corporate Risk Management) where the source text reads as below (emphasis mine, I haven't checked our study note):

@Anuja Please see this recent thread at https://forum.bionicturtle.com/thre...-by-reducing-true-economic-value-which.10388/

... Accounting earnings are also called "reported earnings" and these would be the numbers reported by public companies that are closely followed; for example, earnings per share, is reported earnings per share (EPS). These do matter, but they are determined for the most part by accounting principles and their interpretation. The income statement is mostly a function of such rules, including revenue recognition, matching costs during the period, allocating capital investments, and accrual, just to name a few ideas. The accounting principles are terrifically evolved and logical but the net earnings number will not equal the cash flow during the period. In general, while economic earnings can mean different things (for example, economic value added, EVA, is a specific methodology for "un-raveling" the accounting earnings into a cash-flow based earnings), in general it implies a cash-flow based earnings base; i.e., how much normalized cash flow did the company earn in the period. Or even, what is the sustainable (adjusted) cash flow earned in the period. So, it could start with the accounting pre-tax earnings number and, just for example, it could add back depreciation and amortization which are non-cash charges (expenses during the period that reduce reported pretax income but which were not actually cash spent). There are many of examples of both (i) income statement expenses which do not match the current period cash expense, and (ii) conversely, cash investments or dilution that do not get fully deducted in the current period; e.g., investments are capitalized over multiple periods, so maybe only 10% of an cash investment is deducted in the current period expense; or in technology companies, a big issue is stock option dilution which has an accounting treatment that is very different from its potential economic implication (it is hard to expense derivatives!). So, i would say really simply that accounting earnings are the GAAP/IASB rule-based earnings that, while some discretion is given, are mostly forced while economic earnings is the "priestly art and science" of adjusting those numbers into a more genuine cash-flow based perspective.

Although, Crouhy's point is a narrow subset of this overall general trade-off (between conservative accounting and realistic economics) where he is pointing to the issue in hedging, where hopefully i've setup that thorny problem in the link. Mainly the issue is that a successful hedge is likely to minimize the net volatility (aka, minimum variance hedge in Hull) of two positions combined (the "net portfolio" of 1. the exposure + 2. the hedge instrument) yet the accounting rules (being conservative) might force the recognition of a loss immediately. So maybe the "exposure is profitable" during a period such that the hedge instrument (performing its duty) produces a loss. But maybe the profitable side is unrealized (i.e., unreported on the current income statement) but the hedge loss must be realized/reported currently. In this case, maybe the net contribution to economic earnings is roughly zero (low volatility!) but the reported, current period earnings (accounting) contribution only sees the loss (higher volatility). I hope that's helpful musing! Thanks,

"As a final point, even a well-developed risk management strategy has compliance costs, including disclosure, accounting, and management requirements. Firms may avoid trading in derivatives in order to reduce such costs or to protect the confidential information that might be revealed by their forward transactions (for example, the scale of sales they envisage in certain currencies). In some cases, hedging that reduces volatility in the true economic value of the firm could increase the firm’s earnings variability as transmitted to the equity markets through the firm’s accounting disclosures, due to the gap between accounting earnings and economic cash flows." -- Crouhy, Michel. The Essentials of Risk Management, Second Edition (Kindle Locations 1089-1094). McGraw-Hill Education. Kindle Edition.

@Anuja Please see this recent thread at https://forum.bionicturtle.com/thre...-by-reducing-true-economic-value-which.10388/

... Accounting earnings are also called "reported earnings" and these would be the numbers reported by public companies that are closely followed; for example, earnings per share, is reported earnings per share (EPS). These do matter, but they are determined for the most part by accounting principles and their interpretation. The income statement is mostly a function of such rules, including revenue recognition, matching costs during the period, allocating capital investments, and accrual, just to name a few ideas. The accounting principles are terrifically evolved and logical but the net earnings number will not equal the cash flow during the period. In general, while economic earnings can mean different things (for example, economic value added, EVA, is a specific methodology for "un-raveling" the accounting earnings into a cash-flow based earnings), in general it implies a cash-flow based earnings base; i.e., how much normalized cash flow did the company earn in the period. Or even, what is the sustainable (adjusted) cash flow earned in the period. So, it could start with the accounting pre-tax earnings number and, just for example, it could add back depreciation and amortization which are non-cash charges (expenses during the period that reduce reported pretax income but which were not actually cash spent). There are many of examples of both (i) income statement expenses which do not match the current period cash expense, and (ii) conversely, cash investments or dilution that do not get fully deducted in the current period; e.g., investments are capitalized over multiple periods, so maybe only 10% of an cash investment is deducted in the current period expense; or in technology companies, a big issue is stock option dilution which has an accounting treatment that is very different from its potential economic implication (it is hard to expense derivatives!). So, i would say really simply that accounting earnings are the GAAP/IASB rule-based earnings that, while some discretion is given, are mostly forced while economic earnings is the "priestly art and science" of adjusting those numbers into a more genuine cash-flow based perspective.

Although, Crouhy's point is a narrow subset of this overall general trade-off (between conservative accounting and realistic economics) where he is pointing to the issue in hedging, where hopefully i've setup that thorny problem in the link. Mainly the issue is that a successful hedge is likely to minimize the net volatility (aka, minimum variance hedge in Hull) of two positions combined (the "net portfolio" of 1. the exposure + 2. the hedge instrument) yet the accounting rules (being conservative) might force the recognition of a loss immediately. So maybe the "exposure is profitable" during a period such that the hedge instrument (performing its duty) produces a loss. But maybe the profitable side is unrealized (i.e., unreported on the current income statement) but the hedge loss must be realized/reported currently. In this case, maybe the net contribution to economic earnings is roughly zero (low volatility!) but the reported, current period earnings (accounting) contribution only sees the loss (higher volatility). I hope that's helpful musing! Thanks,

Last edited:

Hello @Anuja

Please note that I moved your thread here, as you had it posted under the "Posting in the forum" thread, which is a thread that explains where you should post questions. I've used the search function to try to find other threads that discuss your question, and I also searched the current FRM curriculum. Can you be more specific about the current reading that you are studying in the FRM curriculum so I can move your post to the correct section of the forum? I was unable to find the terms you have asked about anywhere in the curriculum.

Thank you,

Nicole

Thank you

Hi @Anuja Sure thing, I was reading my feeds this morning and noticed the ATTACHED (as pdf) article in the financial times (article also at https://www.ft.com/content/69599442-73aa-11e7-93ff-99f383b09ff9 but this may be paywalled is why i saved the PDF). It speaks to this topic almost exactly! FWIW, as some of the commentators note, "This debate has been around since the days of Stern Stewart." [i.e., the firm responsible for promoting EVA]. It's really not a new topic but it's interesting that the debate has no clear winner; e.g., you can argue, and cite research, that accrual-based earnings are a superior measure. There are issues beyond Crouhy's specific issue (economic versus accounting volatility) including that the ROIC below both (i) looks at cash-flow and (ii) carefully incorporates the balance sheet so that investments are treated economically. Below is a copy of some of the article (emphasis mine, where i think the key points are made):

"Earnings shenanigans underpin Wall Street record (Return on invested capital paints much less flattering picture of company valuations):

With earnings season under way in the US, investors have been able to judge whether company profits are good enough to justify an S&P 500 index which has repeatedly hit new all-time highs this year.

Last year bearish commentators pointed out that lofty valuations mean optimistic expectations for earnings need at the very least to be matched to avoid a major market tantrum. Superficially, at least, it appears high hopes have been met. The FT reported last week that with almost half the companies in the S&P 500 having reported second-quarter earnings, 73 per cent have beaten analyst expectations, the highest level since FactSet began tracking such data in late 2008.

That will embolden optimists to point to a sustained US earnings recovery that has unfolded since 2016. Don’t expect this to reassure those who have sounded warnings about over exuberance in the US equity markets for years. They will note that the S&P 500 is trading at a multiple of earnings near to the highest in its history, on both a forward and cyclically adjusted basis. Based on the logic of mean reversion they argue a sharp correction is likely.

But as the debate rages on whether earnings will justify current valuations, a critical point is lost: the accounting earnings which are used to construct the widely cited p/e multiples that each camp employs fail to tell the whole story. There are reasons to be sceptical about the apparent current earnings recovery, but not for the reasons that many bulls or bears believe.

Great attention is lavished on the earnings each company releases. Yet published accounting earnings — used by the majority of the market to make their investment decisions — can do a poor job of reflecting the true economic earnings power of a business.

Many highly respected investors instead argue that the returns a company makes on its invested capital are the single most important factor dictating the performance of its shares. As Charlie Munger of Berkshire Hathaway has put it, “Over the long term, it’s hard for a stock to earn much better than the business which underlies it earns.”

Return on invested capital measures the profit a company is generating on every dollar of capital ever invested in its business, and is far trickier to calculate than simple published accounting earnings. It requires trawling back through hundreds of pages of footnotes in annual reports to adjust back all the capital ever invested into a business. New Constructs, an investment research company, bases its entire practice on the superiority of ROIC over the frequent shenanigans found in GAAP earnings. Not only do accounting rules change over time, rendering crude historical comparisons inaccurate, there are multiple ways large US-listed companies can use adjustments and other tricks to massage their quarterly numbers.

Instead of relying on accounting earnings, New Constructs instead calculates the return on invested capital of each S&P 500 member company to gain an accurate assessment of their true economic earnings. Their research shows that the apparent earnings recovery of large US listed companies in recent years that is used to justify the stock market rally may have been something of a mirage.

According to New Constructs, since 2015 reported annual GAAP net earnings for the S&P 500 have increased by 14.6 per cent from $794bn to $910bn. At the same time, its calculation of true economic earnings, which are derived from returns on invested capital, have actually fallen by 5 per cent. What is driving this discrepancy and what does it mean?

These are far from reassuring numbers. The picture they reinforce is that US large companies have been able to grow accounting earnings through financial engineering even though their cash flows are actually flat, or even declining.

This raises troubling questions about the sustainability of the current rally for the majority of US companies. Rather than place all their faith in popular, but flawed, price to earnings ratios, investors and commenters on both sides of the valuation debate would do far better to start focusing more closely on returns on capital."

Attachments

elbest1542

Member

I have a related question regarding chapter 1 (Crouhy et.al) and would be grateful to get an explanation. There is an example about a hypothetical US firm that acquired a plant in the UK (backed by a bank loan denominated in pounds) in the "risk appetite" section of the chapter. So, initially the firm is subject to accounting exposure while being economically hedged -this part I get. The question is: why does the company get exposed to economic risk once it hedges its accounting exposure to pound by shorting futures contracts? I get the definitions of accounting/economic profits but the meaning of economic profit in this particular example escapes me..

Hi @elbest1542 Crouhy doesn't provide a numerical assumption but here is my interpretation. I have copied the relevant section below (emphasis mine):

... If the company buys a futures contract on the pound, it hedges the accounting risk because (eg) depreciation in the dollar which produces reported (accounting) losses on the translated loan will be offset by gains on the futures contract. But while the FX accounting translation loss is not economic, the FX forward gain is economic and reported. However, the FX forward is a symmetrical hedge (unlike say an option): if the dollar appreciates, then the FX forward will produce and economic (and accounting) loss. Under the dollar appreciation scenario, the accounting hedge will still work, as that is its purpose! However, economically it is a loss for the company: the translation economically contributes neither! So my interpretation here is that the FX forward hedge trade by itself is both economically real (which it would be always!) and also has an accounting impact. I hope that's helpful!

"The board should declare whether the aim is to hedge accounting profits or economic profits, and short-term profits or long-term profits. With regard to the former issue, the two measures of profit do not necessarily coincide, and at times their risk exposure is vastly different. Imagine a U.S. firm that purchases a plant in the United Kingdom that will serve U.K. clients, for a sum of £1 million. The investment is financed with a £1 million loan from a British bank. From an economic point of view, the sterling loan backed by a plant in the United Kingdom is fully hedged. However, if the plant is owned and managed by the U.S. company (that is, if it fails the “long arm test” that determines whether a subsidiary should be considered as an independent unit), its value is immediately translated into U.S. dollars, while the loan is kept in pounds. Hence, the company’s accounting profits are exposed to foreign exchange risk: if the pound is more expensive, in terms of the dollar, at the end of the year, the accounts will be adjusted for these financial costs and will show a reduction in profits.

Should the U.S. company hedge this kind of accounting risk? If it buys a futures contract on the pound, its accounting exposure will be hedged, but the company will be exposed to economic risk! In this case, no strategy can protect both the accounting and economic risks simultaneously. (As we hinted earlier, while most managers claim that they are concerned with economic risk only, in practice many corporations, especially publicly traded corporations, hedge their accounting risks in order to avoid fluctuations in their reported earnings.)

It is the board’s prerogative, subject to local regulatory provisions, to decide whether to smooth out the ups and downs of accounting profits, even at significant economic cost. Such a decision should be conveyed to management as a guiding policy for management actions. If the board is concerned with economic risk instead, this policy should also be made clear, and a budget should be allocated for this purpose." -- Crouhy, Michel. The Essentials of Risk Management, Second Edition (Kindle Locations 1236-1251). McGraw-Hill Education. Kindle Edition."

... If the company buys a futures contract on the pound, it hedges the accounting risk because (eg) depreciation in the dollar which produces reported (accounting) losses on the translated loan will be offset by gains on the futures contract. But while the FX accounting translation loss is not economic, the FX forward gain is economic and reported. However, the FX forward is a symmetrical hedge (unlike say an option): if the dollar appreciates, then the FX forward will produce and economic (and accounting) loss. Under the dollar appreciation scenario, the accounting hedge will still work, as that is its purpose! However, economically it is a loss for the company: the translation economically contributes neither! So my interpretation here is that the FX forward hedge trade by itself is both economically real (which it would be always!) and also has an accounting impact. I hope that's helpful!

elbest1542

Member

@David Harper CFA FRM , thank you!

Hi @elbest1542 Crouhy doesn't provide a numerical assumption but here is my interpretation. I have copied the relevant section below (emphasis mine):

... If the company buys a futures contract on the pound, it hedges the accounting risk because (eg) depreciation in the dollar which produces reported (accounting) losses on the translated loan will be offset by gains on the futures contract. But while the FX accounting translation loss is not economic, the FX forward gain is economic and reported. However, the FX forward is a symmetrical hedge (unlike say an option): if the dollar appreciates, then the FX forward will produce and economic (and accounting) loss. Under the dollar appreciation scenario, the accounting hedge will still work, as that is its purpose! However, economically it is a loss for the company: the translation economically contributes neither! So my interpretation here is that the FX forward hedge trade by itself is both economically real (which it would be always!) and also has an accounting impact. I hope that's helpful!

Hi David, I am from an IT background and still feeling confused with the concepts.

I understand buying GBP futures hedged accounting risk. But why it subsequently incurs economic risk? The foreign asset is still backed up by a loan. If GBP rate rises, loss in loan can be covered by gains from futures contract. If GBP rate drops, loss in futures long position will be covered by loan (debt becomes smaller). The asset is always backed up by the loan. The only risk here is the exchange rate in translation of loan, which is hedged by futures contract. So where is the economic risk?

I would really appreciate if someone could thoroughly explain to me this:

'Hedging that reduces volatility in the true economic value of the firm could increase the firm’s earnings variability as transmitted to the equity markets through the firm’s accounting disclosures, due to the gap between accounting earnings and economic cash flows.'

Its been taken from Crouhy, Chapter 2 Corporate Risk Management: A Primer --- Disadvantages of Hedging

Thanks

'Hedging that reduces volatility in the true economic value of the firm could increase the firm’s earnings variability as transmitted to the equity markets through the firm’s accounting disclosures, due to the gap between accounting earnings and economic cash flows.'

Its been taken from Crouhy, Chapter 2 Corporate Risk Management: A Primer --- Disadvantages of Hedging

Thanks

Hi @terrence I think the initial situation is something like a US-based company:

The situation, as I interpret Crouhy's example, is when the company is forced to recognize a gain/loss on the Plant Asset, but will somehow not be recognizing (in the current period at least) the offsetting gain on the liability side. Now the accounting rules have disconnected from the economics. When the dollar appreciates, the loss on the plant asset is recognized but the natural hedge is not respected because the (unrealized) gain on the GBP liability is not paired to the occasion. Now the company may be "forced" to enter the FX contract hedge which serves really to hedge the Plant Asset (i.e., recognized loss on the asset side is offset by futures gain), but economically, when the hedge doesn't work (when the FX produces a loss), all this company has really done is add an extra FX futures contract position to an economically hedged position. Put briefly, the company in the initial situation is fine. But if it is forced to add an FX futures contract, because it must only recognize one side (the asset side) of the natural hedge, in order to maintain accounting neutrality, then all it has economically done is add an FX futures contract to a net neutral situation. That's how I think I interpret this Crouhy example. Thanks,

- on the liabilities side has borrowed GBP £ 1.0 mm in a loan, to fund

- on the asset side: a GBP £ 1.0 mm Plant

The situation, as I interpret Crouhy's example, is when the company is forced to recognize a gain/loss on the Plant Asset, but will somehow not be recognizing (in the current period at least) the offsetting gain on the liability side. Now the accounting rules have disconnected from the economics. When the dollar appreciates, the loss on the plant asset is recognized but the natural hedge is not respected because the (unrealized) gain on the GBP liability is not paired to the occasion. Now the company may be "forced" to enter the FX contract hedge which serves really to hedge the Plant Asset (i.e., recognized loss on the asset side is offset by futures gain), but economically, when the hedge doesn't work (when the FX produces a loss), all this company has really done is add an extra FX futures contract position to an economically hedged position. Put briefly, the company in the initial situation is fine. But if it is forced to add an FX futures contract, because it must only recognize one side (the asset side) of the natural hedge, in order to maintain accounting neutrality, then all it has economically done is add an FX futures contract to a net neutral situation. That's how I think I interpret this Crouhy example. Thanks,

Last edited:

Hi @umerkhan I just replied to a very similar question here (actually, it's an entire thread about this topic). We have a temporary glitch in the forum, we cannot currently move posts, but we'll move your post here (cc @Nicole Seaman) when it's fixed: https://forum.bionicturtle.com/threads/economic-earning-accounting-earning.10625/

Hi @terrence I think the initial situation is something like a US-based company:

This a balance sheet this is "matched in currency exposure." From the parent US company's perspective, say the dollar depreciates (ie, GBP appreciates) over the year. As you suggest, the increase in the dollar-translated cost of the GBP loan Liability is offset (naturally hedged) by the gain on the USD-translated gain on the GBP Plant Asset. Or, if the dollar appreciates, the dollar-translated loss on the plant Asset is offset by the gain on the dollar-translated loan Liability. This is the economics, where the natural hedge requires no FX contract.

- on the liabilities side has borrowed GBP £ 1.0 mm in a loan, to fund

- on the asset side: a GBP £ 1.0 mm Plant

The situation, as I interpret Crouhy's example, is when the company is forced to recognize a gain/loss on the Plant Asset, but will somehow not be recognizing (in the current period at least) the offsetting gain on the liability side. Now the accounting rules have disconnected from the economics. When the dollar appreciates, the loss on the plant asset is recognized but the natural hedge is not respected because the (unrealized) gain on the GBP liability is not paired to the occasion. Now the company may be "forced" to enter the FX contract hedge which serves really to hedge the Plant Asset (i.e., recognized loss on the asset side is offset by futures gain), but economically, when the hedge doesn't work (when the FX produces a loss), all this company has really done is add an extra FX futures contract position to an economically hedged position. Put briefly, the company in the initial situation is fine. But if it is forced to add an FX futures contract, because it must only recognize one side (the asset side) of the natural hedge, in order to maintain accounting neutrality, then all it has economically done is add an FX futures contract to a net neutral situation. That's how I think I interpret this Crouhy example. Thanks,

Even the FX futures position is to hedge the Plant Asset, as we are under a situation the liabilities is disconnected, it is still fully hedged. I don't think I quite understand "when the hedge doesn't work". When there is a loss on Plant Asset, it is offset by gain on FX position. That is perfect. But when there is a gain on Plant Asset, this gain is still offset by the loss of FX position. That becomes not perfect even it is still a fully hedged situation? Or the liabilities is connected again when we have a gain on asset? It sounds really strange to me.

Last edited:

Well, like everybody else, I'm challenged to interpret Crouhy who has not presented a numerical example, unlike Saunders. A numerical example would be immediately clarifying. In today's interpretation, from the text, I've inferred:

- The initial state is a US firm who is long GBP on the asset side (GBP-denominated Plant) and short GBP on the liability side (GBP-denominated loan). The natural hedge.

- He says the Plant (Asset) fails the long arm test, and must experience the FX translation. He writes, "if the pound is more expensive, in terms of the dollar [dharper note: this is not my favorite expression, but I interpret this to mean: GBP depreciation/dollar appreciation], at the end of the year, the accounts will be adjusted for these financial costs and will show a reduction in profits." At this point, the economics of the natural hedge are good, but the "accounting problem" appears to be that the Asset (long GBP) will be realized as a loss if the GBP depreciates/USD appreciates. For example, if the year starts GBPUSD $1.30 and finished $1.20, then the Asset realized a loss due to FX translation. I've inferred that the accounting problem is that the corresponding gain on the liability (due to the short GBP position) is unrealized. (But I'm not 100% certain)

- While I agree with you that when he writes "Should the U.S. company hedge this kind of accounting risk? If it buys a futures contract on the pound, its accounting exposure will be hedged," it sounds like a long FX position on the GBP, but at the same time, it's possible that the language is lazy. It's conceivable he refers to other side of the pair. That is, so far in my interpretation, the exposure is realized loss on the Asset as illustrated by GBPUSD dropping from $1.30 to $1.20; but alternatively, this is exposure to an increase from USDGBP 0.77 = 1/1.30 to USDGBP 0.83 = 1.20, right? But honestly, it's the author's fault IMO for making us work this hard. So far, we don't need a cipher to know that if the exposure is to realized loss on the GBP-denominated Asset, the futures contract hedge is an FX futures contract that gains on GPB depreciation.

- By "hedge not working" (which is my own lazy language), I just meant when the hedge instrument produces a loss (so far, in my interpretation, the FX futures contract would itself lose under GBP appreciation). In that scenario, we have on the Asset side a net hedge that's working because the currency gain is offset by the futures contract loss. But on the liability side, economically our short GPB position (the loan) experienced an economic loss. The "economic problem" created by the accounting solution is that we have three positions: long GBP asset, short GBP asset (i.e., the futures contract), plus short GBP liability. This is why I have learning XLS for everything. My view is that it's the author's fault for being unclear, frankly. If you get a chance to look at Saunder's FX hedge/unhedged illustrations, I hope you'll agree that a simple numerical example is very clarifying. Again, I am not 100% sure about my interpretation. Thanks!

Last edited:

Well, like everybody else, I'm challenged to interpret Crouhy who has not presented a numerical example, unlike Saunders. A numerical example would be immediately clarifying. In today's interpretation, from the text, I've inferred:

- The initial state is a US firm who is long GBP on the asset side (GBP-denominated Plant) and short GBP on the liability side (GBP-denominated loan). The natural hedge.

- He says the Plant (Asset) fails the long arm test, and must experience the FX translation. He writes, "if the pound is more expensive, in terms of the dollar [dharper note: this is not my favorite expression, but I interpret this to mean: GBP depreciation/dollar appreciation], at the end of the year, the accounts will be adjusted for these financial costs and will show a reduction in profits." At this point, the economics of the natural hedge are good, but the "accounting problem" appears to be that the Asset (long GBP) will be realized as a loss if the GBP depreciates/USD appreciates. For example, if the year starts GBPUSD $1.30 and finished $1.20, then the Asset realized a loss due to FX translation. I've inferred that the accounting problem is that the corresponding gain on the liability (due to the short GBP position) is unrealized. (But I'm not 100% certain)

- While I agree with you that when he writes "Should the U.S. company hedge this kind of accounting risk? If it buys a futures contract on the pound, its accounting exposure will be hedged," it sounds like a long FX position on the GBP, but at the same time, it's possible that the language is lazy. It's conceivable he refers to other side of the pair. That is, so far in my interpretation, the exposure is realized loss on the Asset as illustrated by GBPUSD dropping from $1.30 to $1.20; but alternatively, this is exposure to an increase from USDGBP 0.77 = 1/1.30 to USDGBP 0.83 = 1.20, right? But honestly, it's the author's fault IMO for making us work this hard. So far, we don't need a cipher to know that if the exposure is to realized loss on the GBP-denominated Asset, the futures contract hedge is an FX futures contract that gains on GPB depreciation.

- By "hedge not working" (which is my own lazy language), I just meant when the hedge instrument produces a loss (so far, in my interpretation, the FX futures contract would itself lose under GBP appreciation). In that scenario, we have on the Asset side a net hedge that's working because the currency gain is offset by the futures contract loss. But on the liability side, economically our short GPB position (the loan) experienced an economic loss. The "economic problem" created by the accounting solution is that we have three positions: long GBP asset, short GBP asset (i.e., the futures contract), plus short GBP liability. This is why I have learning XLS for everything. My view is that it's the author's fault for being unclear, frankly. If you get a chance to look at Saunder's FX hedge/unhedged illustrations, I hope you'll agree that a simple numerical example is very clarifying. Again, I am not 100% sure about my interpretation. Thanks!

How nice you are! Thanks David!

I just want to post my understanding learnt from the discussions with David here. Maybe it can be useful to the ones who does not have enough business knowledge like me.

Let's assume the company publishes balance sheet at year end, at which time all the assets and liabilities should be translated into USD.

At the initial state, which there is an accounting risk. The company has 2 position:

1. Plant Asset

2. Loan Liabilities

No economic risk here because they are naturally hedged. No matter how USDGBP changed, the current net value of them add up to zero in GBP. The accounting risk is due to different maturity of the asset and liabilities. Just think of the asset is longing front futures contract, while the liabilities is a short of next contract.

If the board intends to hedge accounting risk, they decide to short GBP front futures contract. Now the company has 3 positions:

1. Plant Asset

2. Loan Liabilities

3. Short GBP position

At year end, 1 and 3 are both settled so they are hedged. No accounting risk. But what about the loan? It becomes a net short of GBP. It is indeed an economic risk without hedging.

Let's assume the company publishes balance sheet at year end, at which time all the assets and liabilities should be translated into USD.

At the initial state, which there is an accounting risk. The company has 2 position:

1. Plant Asset

2. Loan Liabilities

No economic risk here because they are naturally hedged. No matter how USDGBP changed, the current net value of them add up to zero in GBP. The accounting risk is due to different maturity of the asset and liabilities. Just think of the asset is longing front futures contract, while the liabilities is a short of next contract.

If the board intends to hedge accounting risk, they decide to short GBP front futures contract. Now the company has 3 positions:

1. Plant Asset

2. Loan Liabilities

3. Short GBP position

At year end, 1 and 3 are both settled so they are hedged. No accounting risk. But what about the loan? It becomes a net short of GBP. It is indeed an economic risk without hedging.

Mr Harper, could you please come up with some easy examples because I was totally unable to understand the difference between these two types of profit. Kindly be precise. Thank you@Nicole Seaman Thanks for looking. The relevant LO is "Evaluate some advantages and disadvantages of hedging risk exposures." under the R2 reading (Crouhy Chapter 2. Corporate Risk Management) where the source text reads as below (emphasis mine, I haven't checked our study note):

@Anuja Please see this recent thread at https://forum.bionicturtle.com/thre...-by-reducing-true-economic-value-which.10388/

... Accounting earnings are also called "reported earnings" and these would be the numbers reported by public companies that are closely followed; for example, earnings per share, is reported earnings per share (EPS). These do matter, but they are determined for the most part by accounting principles and their interpretation. The income statement is mostly a function of such rules, including revenue recognition, matching costs during the period, allocating capital investments, and accrual, just to name a few ideas. The accounting principles are terrifically evolved and logical but the net earnings number will not equal the cash flow during the period. In general, while economic earnings can mean different things (for example, economic value added, EVA, is a specific methodology for "un-raveling" the accounting earnings into a cash-flow based earnings), in general it implies a cash-flow based earnings base; i.e., how much normalized cash flow did the company earn in the period. Or even, what is the sustainable (adjusted) cash flow earned in the period. So, it could start with the accounting pre-tax earnings number and, just for example, it could add back depreciation and amortization which are non-cash charges (expenses during the period that reduce reported pretax income but which were not actually cash spent). There are many of examples of both (i) income statement expenses which do not match the current period cash expense, and (ii) conversely, cash investments or dilution that do not get fully deducted in the current period; e.g., investments are capitalized over multiple periods, so maybe only 10% of an cash investment is deducted in the current period expense; or in technology companies, a big issue is stock option dilution which has an accounting treatment that is very different from its potential economic implication (it is hard to expense derivatives!). So, i would say really simply that accounting earnings are the GAAP/IASB rule-based earnings that, while some discretion is given, are mostly forced while economic earnings is the "priestly art and science" of adjusting those numbers into a more genuine cash-flow based perspective.

Although, Crouhy's point is a narrow subset of this overall general trade-off (between conservative accounting and realistic economics) where he is pointing to the issue in hedging, where hopefully i've setup that thorny problem in the link. Mainly the issue is that a successful hedge is likely to minimize the net volatility (aka, minimum variance hedge in Hull) of two positions combined (the "net portfolio" of 1. the exposure + 2. the hedge instrument) yet the accounting rules (being conservative) might force the recognition of a loss immediately. So maybe the "exposure is profitable" during a period such that the hedge instrument (performing its duty) produces a loss. But maybe the profitable side is unrealized (i.e., unreported on the current income statement) but the hedge loss must be realized/reported currently. In this case, maybe the net contribution to economic earnings is roughly zero (low volatility!) but the reported, current period earnings (accounting) contribution only sees the loss (higher volatility). I hope that's helpful musing! Thanks,

@umerkhan The difficultly is not the distinction between accounting and economic profit: that should be easily understood by any accounting student (accounting profits refers to reported earnings per accounting conventions, which any analyst knows does not equate to cash flow or economic balance sheet changes. Among the primary reasons for this are the matching principle. I don't want to spend current time on illustrating accounting basics). Accounting profits are the result of period (quarterly, annual) reports according to accounting rules; economic profits refer to cash-flows and value-based (even if unrecognized) changes which are the economic "truth." The challenge here is Crouhy (the author) is imprecise with respect to the specific example.

If you want me to further color my interpretation, it has already been nicely summarized by @terrence, but I will illustrate below. Let me say that I think Crouhy's abstract concept is straightforward and fine: he is saying that if the balance sheet is already naturally, economically hedged, then the addition of a futures contract (albeit for accounting motivations; again, this refers to reported earnings) will "unbalance" the natural hedge. If we can understand that concept, then we can imagine other permutations, in addition to mine below.

I have three steps, they correspond to the above descriptions (I am using modifications of my learning XLS for the Saunders FX reading; Saunders is precise.)

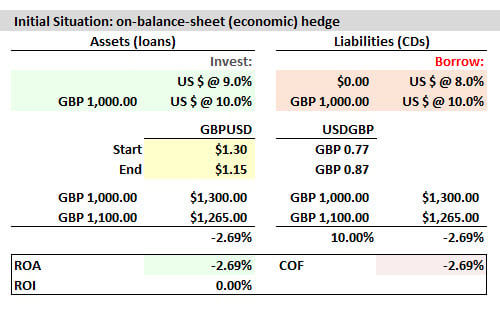

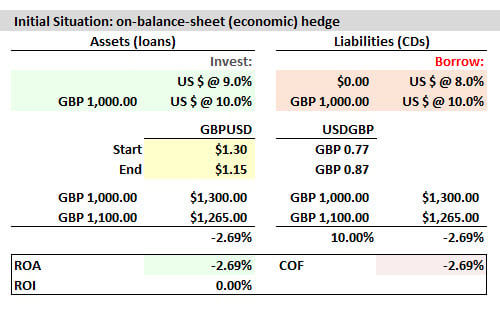

1. The initial state is short GPB (the loan liability) matched with the GPB Asset; below illustrates the GPB 1,000 loan funds the GPB asset, but there is a GBP depreciation (USD appreciation) from $1.30 to 1.15.

The loss on the asset is offset by the negative COF.

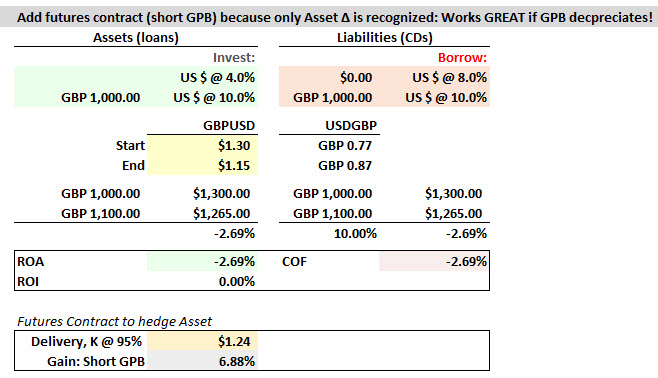

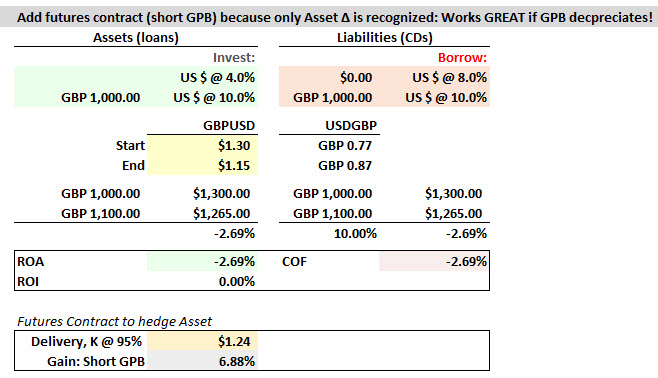

2. My mere interpretation of Crouhy's imprecise language is that the company, for unstated reasons (this gets into accounting and hedge accounting ) must "realize" the loss on the asset due to FX translation; by "realize" I mean "report on the quarterly/annual accrual-based income statement." But if the company only realized the asset loss, it suffers on its accounting profit. So, to hedge the accounting problem, the company adds a FX forward contract position. In my example, the strike price is a 5% discount to the $1.30 and so the company gains on the futures contract. The company's "accounting profit" exposure is represented on the left hand side only; its economic reality includes all three positions (liabilities, assets + FX forward contract). But in this situation, the company's economics are better than before due to the additional +6.88%. Yay for good news!!!

3. Except ooops forward contracts go both ways, uh oh. If the GBP instead appreciates (as below, to $1.45), the accounting is still fine (left hand side only), but the economic (total) situation is worse. I think that's what he means. Here is my XLS: https://www.dropbox.com/s/2s54iy6s4rfawhh/082118-crouhy-hedge-accounting.xlsx?dl=0 if you want to explore this with yet more precision

forward contracts go both ways, uh oh. If the GBP instead appreciates (as below, to $1.45), the accounting is still fine (left hand side only), but the economic (total) situation is worse. I think that's what he means. Here is my XLS: https://www.dropbox.com/s/2s54iy6s4rfawhh/082118-crouhy-hedge-accounting.xlsx?dl=0 if you want to explore this with yet more precision

If you want me to further color my interpretation, it has already been nicely summarized by @terrence, but I will illustrate below. Let me say that I think Crouhy's abstract concept is straightforward and fine: he is saying that if the balance sheet is already naturally, economically hedged, then the addition of a futures contract (albeit for accounting motivations; again, this refers to reported earnings) will "unbalance" the natural hedge. If we can understand that concept, then we can imagine other permutations, in addition to mine below.

I have three steps, they correspond to the above descriptions (I am using modifications of my learning XLS for the Saunders FX reading; Saunders is precise.)

1. The initial state is short GPB (the loan liability) matched with the GPB Asset; below illustrates the GPB 1,000 loan funds the GPB asset, but there is a GBP depreciation (USD appreciation) from $1.30 to 1.15.

The loss on the asset is offset by the negative COF.

2. My mere interpretation of Crouhy's imprecise language is that the company, for unstated reasons (this gets into accounting and hedge accounting ) must "realize" the loss on the asset due to FX translation; by "realize" I mean "report on the quarterly/annual accrual-based income statement." But if the company only realized the asset loss, it suffers on its accounting profit. So, to hedge the accounting problem, the company adds a FX forward contract position. In my example, the strike price is a 5% discount to the $1.30 and so the company gains on the futures contract. The company's "accounting profit" exposure is represented on the left hand side only; its economic reality includes all three positions (liabilities, assets + FX forward contract). But in this situation, the company's economics are better than before due to the additional +6.88%. Yay for good news!!!

3. Except ooops

forward contracts go both ways, uh oh. If the GBP instead appreciates (as below, to $1.45), the accounting is still fine (left hand side only), but the economic (total) situation is worse. I think that's what he means. Here is my XLS: https://www.dropbox.com/s/2s54iy6s4rfawhh/082118-crouhy-hedge-accounting.xlsx?dl=0 if you want to explore this with yet more precision

forward contracts go both ways, uh oh. If the GBP instead appreciates (as below, to $1.45), the accounting is still fine (left hand side only), but the economic (total) situation is worse. I think that's what he means. Here is my XLS: https://www.dropbox.com/s/2s54iy6s4rfawhh/082118-crouhy-hedge-accounting.xlsx?dl=0 if you want to explore this with yet more precision

Last edited:

Similar threads

- Replies

- 1

- Views

- 461

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 108

- Replies

- 1

- Views

- 271

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 116